The Carmalarky Dispatch #03

Lessons from a Saab Garage

Owning a foreign car in Woodstock, Georgia during the 1980s was unusual enough, but driving a Saab made me stand out even more. Saabs were seen as weird cars for weird people. But I’d read that they were “an acquired taste, like olives,” and that sounded right. This was a car made for me. And working at a garage that specialized in Saabs? That was downright eccentric.

But it was also practical, as I had recently purchased a used Saab 99, and it needed regular attention. This was my coming-of-age car, and after many visits to the garage for repairs, I asked the shop owner for a job to help pay the bills. I wasn’t expecting much—just an opportunity to keep my car on the road. But what I got was something much bigger.

The garage, fittingly named Saab Parts & Repair, had once been Georgia’s first Saab dealership,* and was run by a man named David Wolfe. He was originally from Indiana—tall, lanky, and in his early thirties. To me, at seventeen, that was old! But I looked up to him.

Wolfe had a quirky, offbeat energy—goofy one moment, deadpan the next—and a kind of intensity that made him interesting to be around. He wasn’t your typical grease-stained mechanic, nor did he fit the standard of the Southern men I had grown up with, who were loud, conservative, and dismissive of things foreign. Wolfe was smart, curious, and surprisingly well-read. He’d gone to college and carried himself like someone who thought deeply about things.

When I asked him why he liked Saabs, he didn’t talk about style or status. He told me he enjoyed the challenge of driving an underpowered car* and how it required real effort and attention to get the best performance. “You have to work with the car to get something out of it,” he said. “It’s not just stomping the gas pedal. It’s about timing, rhythm, and knowing what the car can do.” That idea stuck with me. It was the first time I’d thought about driving as something you actively did, not just something that happened when you pressed a pedal.

Besides driving underpowered cars, Wolfe liked old trucks, motorbikes, college radio, blues music, and deer hunting, though atypically so. He once told me his favorite part of hunting was being alone in the quiet of the woods, passing time in a deer stand, but not necessarily shooting anything. Later I understood he saw himself as a nerd, but I didn’t see it that way. Wolfe could fix just about anything with wheels, and to me, that was powerful. Plus he owned the shop, made decisions, and had the last word. Though I didn’t know the type at the time, Wolfe would represent the first “renaissance man” I’d met in real life.

David Wolfe had real racing credentials: he was the crew chief for this Saab 900 Turbo that won the 24 Hours of Nelson Ledges, and he also raced in Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) events. He spent hours obsessively dialing in every detail of the winning Saab, determined to make it unstoppable.

Photo from Road & Track, October 1980

Two other mechanics worked there: Bob, with his blond, floppy hair and casual, confident attitude, reminded me of Andy Travis from WKRP in Cincinnati. And John, who was younger, quieter, and always generous with me. He involved me with repairs, offered his time and advice when I started working on my own car, and patiently answered my questions. Fixing cars together felt like a shared mission, like being part of a crew. Since David Wolfe and I shared a first name, they started calling me “The Kid.” I didn’t argue. I guess I was.

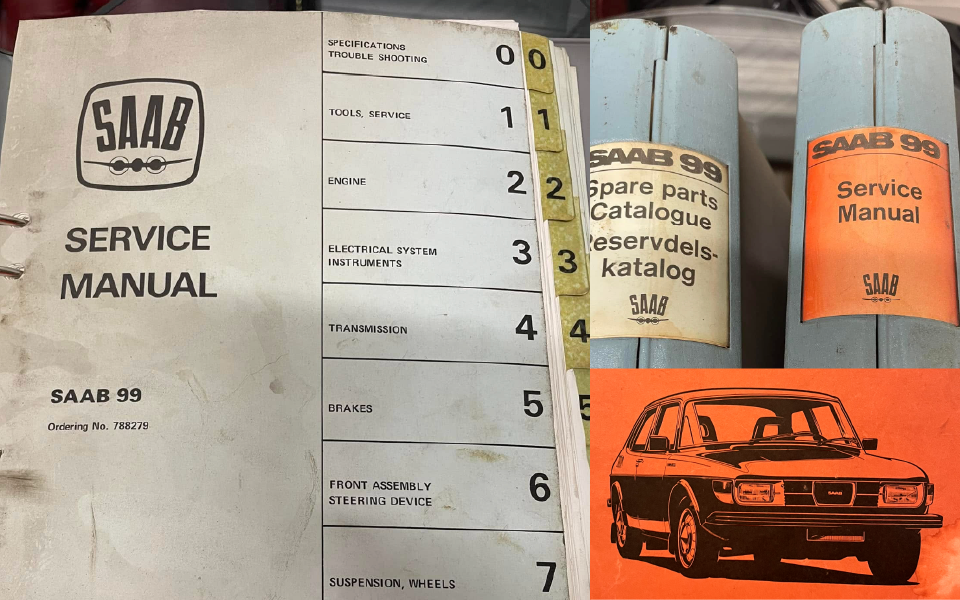

At first, I handled basic tasks: sweeping floors, taking out the trash, answering the phone. For most calls, I had little to offer beyond putting Wolfe on the line. But I was obsessed with Saabs, so just being there felt like heaven. Everywhere I looked were Saab parts, Saab signs, Saab manuals, Saab magazines. A steady stream of Saabs and their owners rolled through the shop, giving me insight into the kinds of people who loved these cars—not just architects, academics, and yuppies. I devoured it all.

Occasionally, I’d meet some of the women in Wolfe’s life. At first, I assumed they were customers, but later I realized there was more to the story. They were educated, bookish types from the nicer parts of Atlanta, like Southern gothic characters from an unreleased Woody Allen film. I couldn’t quite figure it out: What did these intriguing women see in him? It challenged my assumptions—about him, about them, and about how someone could be into both auto mechanics and graduate-level conversation.

More often, I’d meet his friends—men his age, into cars and motorbikes—who hung around the garage after hours, drinking beer, talking shop, and tinkering on projects until it was time to go. They were men I respected. I wanted to be included, but as a New Wave kid in the ’80s, fitting in with men who’d come of age in the ’60s wasn’t easy. I talked too much. My Roxy Music cassettes were from the wrong era. Simon Le Bon was my sartorial guiding light. Still, I was eventually accepted. The work I was doing made me feel like I’d earned it.

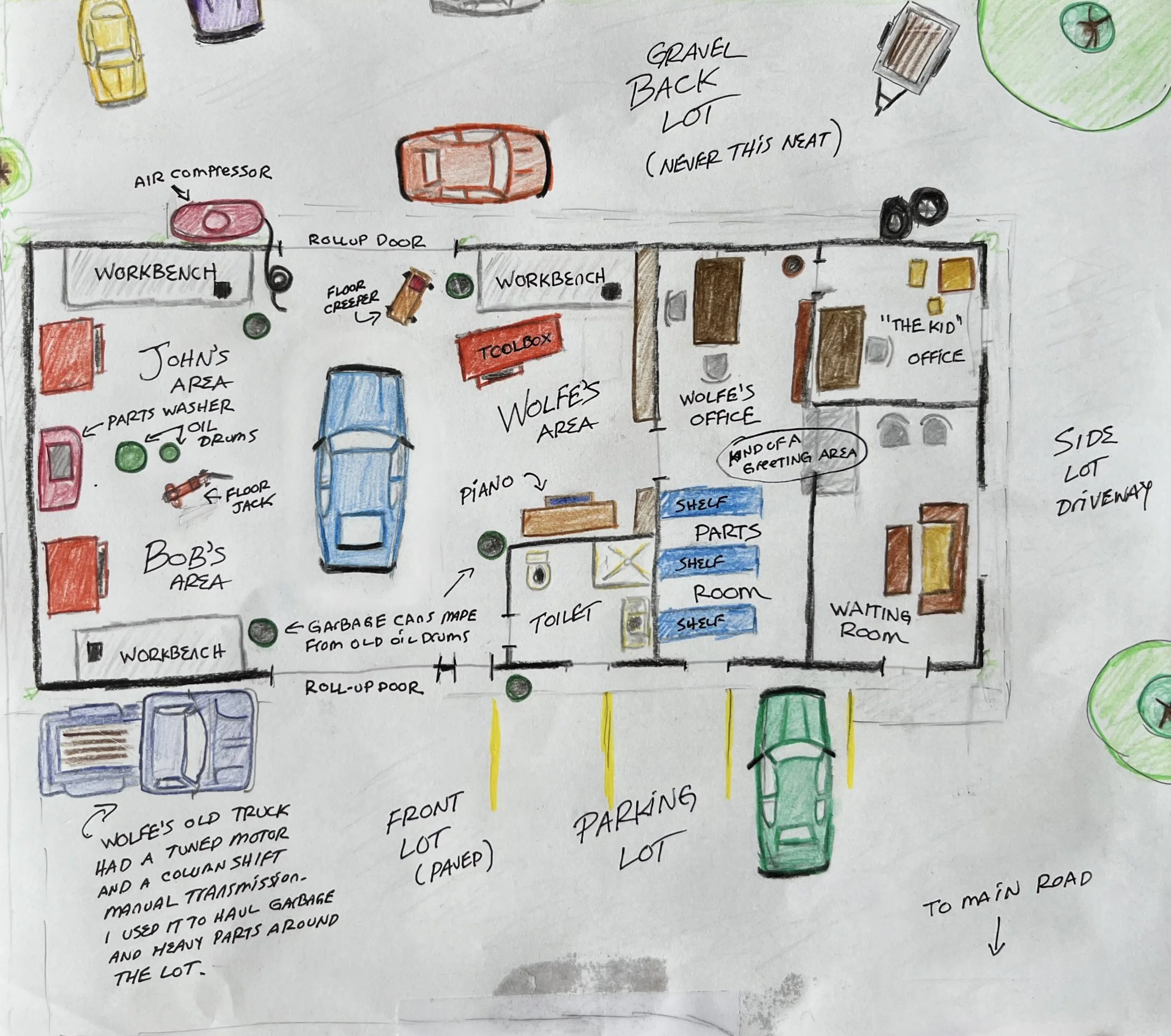

A floor plan I made for this essay.

Garages aren’t quiet, sterile places. The air compressor would fire up without warning—groaning, rattling, then humming—cutting through any conversation. Tools shouted their presence: the sharp chatter of an impact wrench, the rising whine of a drill, the occasional clang of a dropped socket echoing across the floor. The smell was a mix of grease, motor oil, brake cleaner, and sweat. You didn’t just spend time in the garage—you wore it. It came home with you, soaked into your clothes, skin, and hair.

The shop had three cramped service bays, a small office for Wolfe, another for me, a cluttered parts room, and a rudimentary waiting area. It was a cacophony of quirky masculinity, the kind of place where men kept everything their mothers wouldn’t allow in the house. Having never seen another garage, this place defined what I thought one should be.

Dusty shelves held racks of service manuals and automotive ephemera: bins of nuts, bolts, fasteners, coils of wire, stained shop rags, and hastily-scribbled notes set aside for “later.” Against one wall stood an upright piano, topped with a vintage stereo, stacks of magazines, racing trophies, and a taxidermied pheasant—essentials, apparently, for running a garage.

Wolfe, Bob, and John each had their own workbench and a rolling toolbox—always red—covered in stickers for engine lubricants and radio stations. Photos of young women wearing cutoff shorts, crop tops, and suggestively holding impact wrenches adorned wall calendars advertising shop tools. We even had a cat. A shop cat! Kind of ridiculous, but Wolfe seemed genuinely happy with this feline novelty.

Out back, an unpaved lot held a graveyard of Saabs and other makes—parts cars, mostly. Near the far end, the terrain sloped away into a tangle of kudzu, creeping over the bodies of vehicles left behind. I spent hours picking through them to find parts we needed for repairs. Each salvaged piece felt like a prize, carefully returned to usefulness. I especially loved rooting through gloveboxes and trunks, where I’d find matchbooks, receipts, pencils, coins—small bits of other people’s lives.

It was a cacophony of quirky masculinity, the kind of place where men kept everything their mothers wouldn’t allow in the house.

Though I loved cars, I knew almost nothing about fixing them, let alone how to run a business, talk to customers, or work alongside adults who weren’t relatives or teachers. But I was a quick study. I looked for ways to be helpful: organizing boxes of parts, ordering replacements, learning what went into each repair. Eventually, I learned to work on my own car, doing oil changes, brakes, and basic service items like spark plugs and filters. The tactile nature of auto repair suited me: hefting tools, swinging a rolling jack across the concrete floor, thumbing through a service manual, my hands dirty with oil and grease.

When my Saab’s worn transmission started whining for attention, it had to be removed for repair, along with the engine—a job that felt too herculean to even imagine. So I began the disassembly, and with each part I disconnected, my sense of finality grew: How will this ever go back together? After hours of relentless work, I stood over the car, staring into an empty engine bay, its vital organs suspended by a chain nearby.

To find the source of the whining noise, I had to go deeper: splitting open the transmission, removing bearings, cleaning gears, and arranging parts across the workbench. Taking something apart piece by piece felt transformative—not just mechanical, but philosophical. Slowly, carefully, each item was inspected for signs of wear. When the problem is finally revealed, the questions are: Do you clean the part and reuse it? Take the time to repair it? Or replace it altogether?

During that process, I began to understand what Wolfe seemed to know: that the goal wasn’t just to fix a problem and get a car running, but to do the work right. To pay attention. To understand what each part was doing and why. It was the kind of thoughtful engagement that Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance* calls “quality,” a kind of harmony between you, the machine, and the work itself. I came to appreciate that.

My skills as a mechanic grew in that small garage, and so did my skills as a human being. I learned that fitting in doesn’t have to mean blending in; that not all Southern men fit the redneck caricature I carried in my head; and that I could be a person who pays attention, takes care, and gets things working again.

Footnotes

*Georgia’s first Saab dealership

The shop began in 1976 as Complete SAAB Sales and Service, founded by the late Coke Elliott, a legend in Saab sales and racing across the Southeast. Elliott was clearly a mentor to Wolfe, and the shop even prepared official factory race cars for Saab USA.

*he enjoyed the challenge of driving an underpowered car

This is now commonly called “driving a slow car fast”, often attributed to James May, but certainly understood by anyone who enjoys the experience of pushing a less powerful car to its limits, finding it more engaging than driving a very powerful car at a slower pace.

*Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Robert Pirsig’s 1974 philosophical novel uses a cross-country motorcycle trip to explore the idea of “quality,” a state of engagement where craftsmanship, thought, and care converge.

Saab service manual photos from Bjarki Clausen of SAAB in Iceland.

If You Submitted

Be patient dear submitters! We are finalizing our first issue’s contents and will be getting back to you sometime in July. We are working hard to make Carmalarky the best that it can be and we are so honored that you—writers, artists, and friends from all over the world—are willing to give us car geeks and first time publishers your trust. We said, “hey, we are starting this little car-centric literary magazine, come on over” and you said, “Absolutely!” How lucky are we?

A Cross-Country Road Trip

I (Marnie) just drove my 2016 Porsche Cayenne S, that is pushing 100,000 miles, across the country from Los Angeles, California to Satellite Beach, Florida. I am leaving that car, affectionately known as Petunia, in Florida to be the beach-house surf truck. I am already grieving not having her in Los Angeles, where I don't know anyone who doesn’t have a co-dependant relationship with their car.

Petunia’s perforated leather seats have been a great place to cry, scream into the void, take my daughter to college, rally across the desert from surf to snow with all the gear, engage in deep personal conversations without looking at each other, listen to books, and learn all of the lyrics to Billy Joel’s “Italian Restaurant.” Her wayback holds all the stuff (specifically for this trip: two boxes of books, a vintage cruise ship deck chair, a teak desk, curtains, bedding, two duffel bags, luggage, and some other flotsam and jetsam for the house) with grace. She is a team of 430 horses and carriage all in one. I will miss her. Someday I will drive her westward in a return trip across the country, taking twice the amount of time and visiting more friends.

As I sappily detach myself from my daily driver I leave you with something more pragmatic: what I packed for this most recent road trip. Because I love a list.

Sustenance

Stanley Thermos of hot gyukoro green tea (my favorite is from Ocha and Co, or Chado). It was still hot on the second day!

Two almond butter and jelly sandwiches on whole grain bread

Two Fuji apples

Two packages of Justin’s dark chocolate peanut butter cups

A large Yeti travel cup full of many made-at-home shots of espresso and Laird’s SuperFood Creamer (unsweetened liquid version but the sweet cream is my favorite)

Three bottles of drinking water in various sizes

A Starbuck’s Egg Bite which, outside of something homemade, is one of the easiest things to eat while driving (no crumbs), with an Iced Matcha with soy milk (twice)

Veggies with Lipton’s onion dip

Dagwood-style sandwiches made at my sister’s house in Colorado

A fabulous home-cooked meal in Lawrence, Kansas with my dear friends the Haveners

Other Essentials

My cooler is a Yeti lunch bag kind of like this one from our friends at The Surfer’s Journal.

An L.L. Bean Boat and Tote that I’ve had since 2005 holds non-perishables. I strapped them both in on the passenger front seat with the seatbelt (for safety) within easy reach.

I also keep a couple of cotton scarves that David brought me from Cambodia in the car for covering seats, wiping hands, and protecting laps. I affectionately call them my schmattes in honor of my friend Gary who reminded me that I could either tough life out or “grab my bindle stick and schmatte and hit the road.” It also reminds me of Arthur Dent’s towel in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series by Douglas Adams (an epic road trip across space).

My California emergency “go bag” which is an old North Face hiking fanny pack from the 90s filled with a change of underwear, old puffy jacket, wool hat, water packets, matches, knife, first aid kit, granola bars, emergency blanket, hydration tablets, and a bandana.

Audio books. I love listening to novels by Tim Dorsey who makes me laugh out loud. He is another master of the Florida story like Carl Hiasen, Dave Barry, and Lauren Groff but weirder: strange and lovable characters, insane crime sprees, wacky plot lines, and many barely believable hijinks. But the best thing I’ve listened to recently on the road is Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalls. Brilliant and under four hours long.

My sister, Paula. As adults, we do all of the things on our road trips that Zoltan (our dad) wouldn’t let us do during childhood drives from Florida to North Carolina like take bathroom breaks, buy and eat junk, drink water, play whatever music we want, and eat messy food. It is good for my soul to spend alone time with her.

My Favorite Section of the Drive

(besides pulling into friends and family driveways)

Richfield, Utah to Denver, Colorado: I woke up crazyearly at the Marriott Fairfield Inn and nothing was open so I ate my second apple and drank green tea out of the Stanley top cup as I drove out of Richfield. The views are stunning, the rest stops could qualify as their own national parks, and on this trip, the roads were empty as I watched the sun rise over I-70 and Fishlake National Forest. If you ever travel this way, take an hour or two to walk through the Pando Aspen Clone. I listened to The Maltese Iguana by Tim Dorsey (his last book before he died in 2023) for company. I felt like the only person on the planet.

Love what you’ve read? Share The Carmalarky Dispatch with fellow car lovers, storytellers, and adventurers! Forward this one and tell them to sign up for the next one. Let’s grow the Carmalarky community and celebrate the stories that keep us moving.